Vietnam Group Ops Failure Points | Mitigation for Agents

Common Failure Points in Vietnam Group Operations (and How Professionals Mitigate Them)

Operational breakdowns in Vietnam group travel rarely come from a single mistake; they usually arise from unclear ownership, weak supplier controls, and incomplete documentation across the agency–DMC–supplier chain. This industry-wide reference on Common Failure Points in Vietnam Group Operations (and How Professionals Mitigate Them) clarifies where governance typically fails, who holds decision authority at each stage, and what must be agreed and recorded before departure. It is designed to help travel professionals set defensible expectations, protect duty-of-care standards, and reduce disputes when disruptions occur on the ground.

1. Context and relevance for Common Failure Points in Vietnam group operations

Vietnam group programs (leisure, MICE, incentive) amplify operational risk because delivery is inherently multi-supplier and multi-city. A single program can rely on hotels, coaches, venues, restaurants, guides, and activity operators - each with separate operating norms, confirmation behaviors, and escalation responsiveness. Add variable traffic conditions, weather sensitivity for outdoor and water-based activities, and handoffs between cities, and the system becomes highly dependent on disciplined coordination.

Failure points become commercial issues when assumptions are misaligned on three questions: who pays, who decides, and who communicates to the end client. A delay or cancellation is rarely “just operational” if incremental costs were not pre-authorized, decision authority was not defined, or client messaging diverges between parties.

In governance terms, “professional mitigation” means predefined control points, escalation rules, and audit-ready documentation - not ad hoc heroics. The objective is predictable execution under contract: clear triggers, clear authority, and traceable decisions that stand up to procurement review and duty-of-care expectations.

Used correctly, this reference supports planners by strengthening SOWs, clarifying responsibility ownership, and enabling objective post-incident reviews without supplier blame narratives. Incidents are treated as managed events with documented decisions, rather than as failures explained after the fact.

Scope boundaries: this article focuses on inbound group operations and partner coordination in Vietnam (agency–DMC–supplier chain). It does not provide retail travel advice and does not function as destination marketing.

2. Roles, scope, and structural considerations

Core role definitions used in Vietnam group logistics governance

Destination Management Company (DMC): A locally-based service provider responsible for on-ground execution, supplier management, and real-time coordination under a B2B contract. The DMC typically operates under the sending party’s brand and does not usually hold the end-client contract directly.

Travel agency / tour operator (sending party): The B2B entity that holds the client relationship and booking contract, captures requirements, and remains responsible for client-facing communication and stakeholder management.

Suppliers: Hotels, transport operators, restaurants, venues, guides, and activity providers contracted to deliver specific services and service levels.

End client: The corporate group, incentive group, or leisure group receiving services in Vietnam.

Responsibility boundaries that reduce disputes (high-level ownership logic)

Requirements capture: the sending party leads, because it owns the client contract. The DMC validates feasibility, flags gaps, and translates requirements into executable specifications.

Supplier selection/contracting: the DMC executes supplier engagement on behalf of the sending party, with explicit approval checkpoints when supplier choice, cancellation terms, or service level affects client outcomes or budget exposure.

On-ground logistics and incident activation: the DMC acts immediately for operational safety and continuity; the sending party remains client-facing and owns the narrative to the end client, supported by verified operational updates.

Documentation and audit trail: a shared obligation. The DMC maintains operational logs (confirmations, incident timelines, supplier correspondence), while the sending party retains the client communications record and approval evidence.

Structural considerations specific to Vietnam DMC operations and planning

Supplier confirmation culture varies by city/season: confirmation discipline cannot rely on informal assurances. Written confirmation becomes a governance requirement when demand is high or when service is time-critical.

Group movement constraints: coach capacity, luggage handling, venue timing windows, and guide-to-logistics command chain influence feasibility. Programs fail when timing is designed without operational buffers or when “who calls whom” is not defined on the day.

Decision authority design: the contract-to-delivery model must specify who can cancel/reschedule, approve substitutions, or authorize incremental costs - and under what triggers. Without this, real-time response is delayed or disputed.

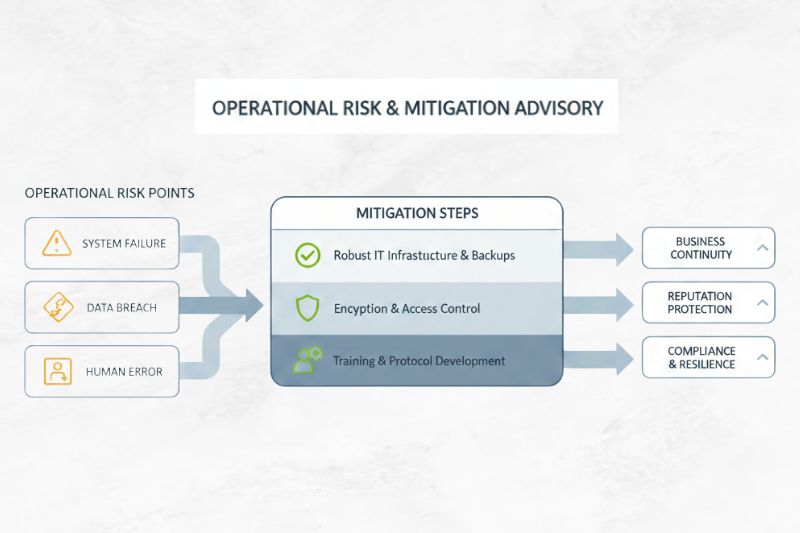

3. Risk ownership and control points

Where failures typically occur in the program lifecycle

Pre-booking: incomplete briefing packs, feasibility gaps, missing special requirements (mobility, dietary, medical), and unclear cost tolerance for contingencies.

Pre-departure: late rooming lists, unconfirmed suppliers, and contingency readiness that exists conceptually but is not approved, budgeted, or callable.

In-operation: transport disruption, weather cancellations, medical incidents, supplier no-shows, and accommodation mismatches - often compounded by delayed escalation or unapproved substitutions.

Post-incident: missing logs, unclear cost responsibility, and inconsistent client narrative (what happened, why decisions were taken, and who approved what).

Risk ownership map by disruption type (governance view; not a comparison table)

Flight disruption/late arrival: the agency owns air arrangements and airline liaison. Once notified with revised ETA, the DMC owns ground adjustments (transport timing, late check-in coordination, pre-agreed meal/rest provisions if activated).

Hotel overbooking/rooming mismatch: the DMC owns supplier performance enforcement and immediate resolution logistics; the agency owns client-facing narrative and expectation management, supported by written confirmation evidence and incident logs.

Medical incident: the DMC owns immediate on-ground response coordination (medical facility, transport, local handling). The agency owns insurance liaison and stakeholder communications (client contact, employer, family/emergency contact), based on verified incident details.

Coach breakdown/traffic delay: the DMC owns transport provider management, impact assessment to downstream services, and contingency activation if triggers are met.

Weather disruption: the DMC owns feasibility assessment with operators and activation of pre-approved alternatives. The agency owns expectation-setting and approvals (especially when the experience or budget changes materially).

Supplier no-show: the DMC owns confirmation discipline, substitutions, and contractual follow-up. The agency approves material changes if required by the SOW or client policy.

Preventive controls that anchor “professional mitigation”

Briefing pack completeness and sign-off rules: objectives, constraints, special requirements, and cost tolerance must exist before supplier confirmation. Missing constraints become liabilities during disruption.

Written supplier confirmations with service specs: time, scope, contacts, and cancellation terms must be confirmed in writing. “Confirmed” should mean “auditable,” not “assumed.”

Change-control triggers: define what requires re-approval (group size shifts, timing changes, property changes, budget deltas, added requirements). Without triggers, silent scope creep erodes supplier enforceability.

Pre-agreed contingency framework: define substitution boundaries, decision authority, and incremental cost rules in advance. A contingency that cannot be authorized quickly is not operationally usable.

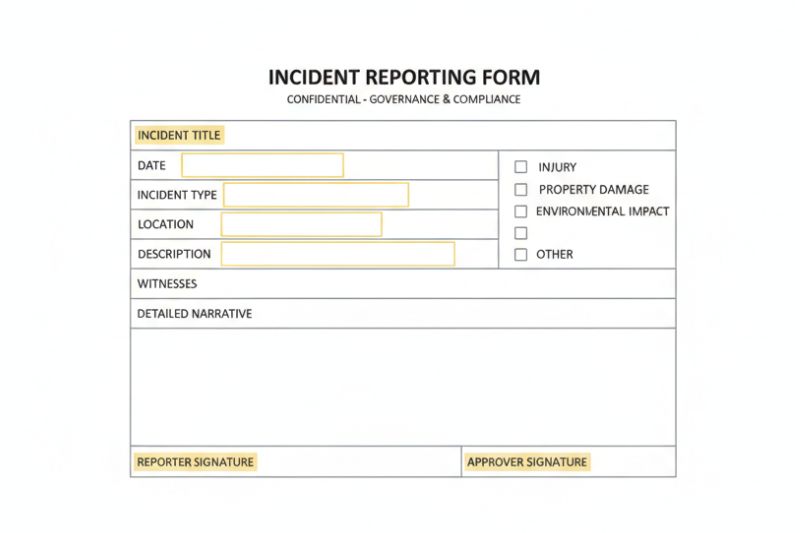

Escalation logic and documentation expectations (audit-ready, shared)

Escalation chain design: guide → DMC ops manager → agency lead → client stakeholder. The chain should be written, with primary and backup contacts, and aligned to incident severity (safety vs service).

Minimum incident log elements: time/location, impact, actions taken, communications timeline, resolution, cost impact, and root cause notes where feasible. The purpose is defensibility and learning, not attribution.

Sign-off discipline: DMC incident report + agency acknowledgment + supplier response when applicable. This closes ambiguity on “what was known when,” and “who approved what.”

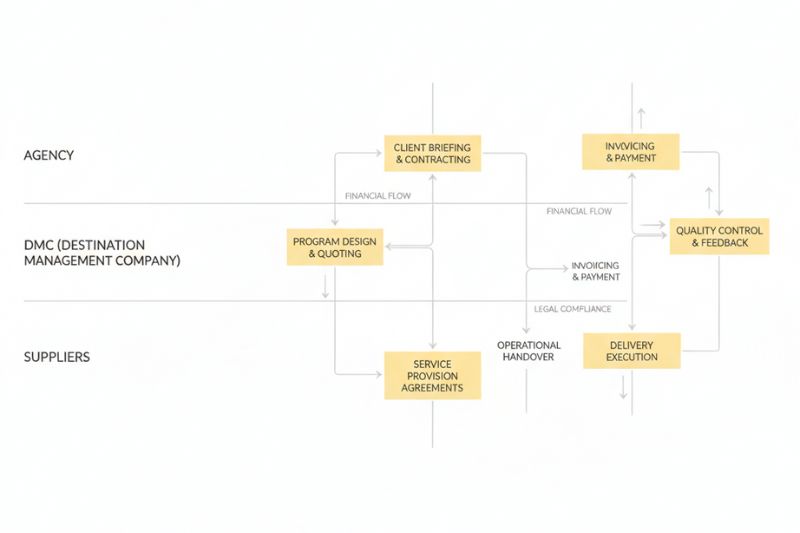

4. Cooperation and coordination model

Contract-to-delivery cooperation model (industry-wide)

Agencies and DMCs reduce avoidable failures when they formalize three interfaces: (1) a requirements validation call to translate client goals into service specifications, (2) approval checkpoints before supplier confirmation and before any material substitutions, and (3) decision rights for disruption handling (who can authorize what, under which triggers).

Supplier management boundaries should be explicit: the DMC negotiates and enforces supplier delivery, but the agency approves material substitutions that affect client experience, brand constraints, or budget exposure - unless pre-authorized under a contingency framework.

Communication discipline for Vietnam group operations

A communication matrix should define primary and backup contacts, response-time expectations, and escalation triggers differentiated by category (safety/medical vs service/timing). This prevents delayed response and prevents conflicting instructions during high-pressure moments.

Channel governance matters: establish one “source of truth” thread for operational updates (and specify what must be logged via email for audit). Avoid single-person dependency by ensuring backups are included and responsibilities are role-based, not personality-based.

Client communication boundary should be protected: the agency remains the primary voice to the end client. The DMC should supply verified status updates, confirmation receipts, and incident timelines so that client messaging is consistent and defensible.

Shared governance artifacts that reduce operational ambiguity

Centralized confirmation log: a timestamped repository of supplier confirmations, contacts, service specs, and cancellation terms.

Rooming list control process: deadline, versioning, and change approvals so hotels are not working from outdated manifests.

Daily operations rhythm: structured briefings, handoffs between guides and logistics, and end-of-day status capture to prevent silent drift in timing and commitments across cities.

5. Vietnam DMC operations and planning: briefing packs, change control, and incident logs that prevent group failures

Briefing pack requirements that correlate with fewer breakdowns (what must exist before supplier confirmation)

Client profile & objectives: group composition, mobility/dietary needs, and brand or corporate culture constraints for MICE/incentives. Objectives should be stated as operational requirements (what must be true on the ground), not only as themes.

Logistical specs: arrival/departure windows and flexibility, hotel category and room configuration requirements, transport constraints (capacity, luggage, accessibility), and any activity exclusions that must be respected.

Risk & contingency expectations: acceptable delay thresholds, which items are weather-dependent, medical/insurance details required for response coordination, and cost responsibility rules for contingency activation and incremental spend.

Communication & escalation: 24/7 contacts (role-based), decision authority for cancellations/substitutions, and reporting cadence (daily status vs incident-only) so both parties know what “good communication” means operationally.

Approval & sign-off: itinerary approval, manifest/rooming list approval, budget tolerance (what requires re-approval), and explicit acknowledgment of special requirements so they are not treated as “best effort.”

Change-control rules (what triggers re-approval and why it matters operationally)

Material changes typically include group size variance, timing shifts, hotel/property changes, transport provider changes, and scope additions/removals (activities, meals, venues). In operational terms, these changes can invalidate prior confirmations, alter capacity requirements, or trigger new cancellation exposures.

The governance rationale is straightforward: change control prevents silent scope creep and protects supplier enforceability in peak-demand periods when availability is constrained and “informal flexibility” is not reliable.

A defensible documentation trail should include: a change request, cost/impact statement, approval record, updated itinerary/specification, and supplier reconfirmations where affected. Without this chain, disputes tend to focus on perceptions rather than on recorded decisions.

Incident logging and audit trail as a duty-of-care tool (not just a dispute tool)

For duty-of-care governance, every incident - even when resolved quickly - benefits from a minimum standardized dataset: timestamps, roles, actions, communications, and outcome. Standardization makes incidents comparable across programs and reduces “narrative drift.”

A post-incident review model should focus on corrective actions, supplier performance notes (fact-based), and preventive measures for future groups. The output is a governance improvement plan, not a blame allocation exercise.

Partner success/case-study potential (without stories)

For internal procurement and QA, agencies can capture operational performance indicators such as response time categories, confirmation completeness, substitution frequency, and incident closure time - provided definitions are agreed in advance and measured consistently.

Agencies can also use documentation to justify decisions to clients: rationale for cancellations, substitutions, and contingency spend approvals. The credibility comes from timestamps, written confirmations, and approved decision rights - not from post-event assertions.

6. FAQ themes (questions only, no answers)

- Who owns cost responsibility when a disruption crosses boundaries (airline delay triggering hotel/meal costs)?

- What documentation is considered minimum acceptable proof of supplier confirmation in Vietnam group operations?

- When should a DMC be authorized to activate contingency suppliers without prior agency approval?

- What change-control triggers most commonly invalidate prior supplier confirmations or room allocations?

- How should decision authority be defined for weather cancellations and activity substitutions?

- What is the correct escalation chain for medical incidents, and who communicates with insurance and family/employer?

- How can agencies audit a DMC’s incident logs and confirmation logs without duplicating operational work?

- What operational checkpoints best predict hotel overbooking/rooming mismatch risk for groups?

- How should transport buffer assumptions be documented to avoid disputes over “missed” activities?

- What should be included in a post-incident report to support procurement review and future supplier decisions?

EN

EN