Vietnam Supplier Payment Terms for Agents | Risk Controls

Vietnam supplier payment terms agents: governance, responsibility boundaries, and audit-ready settlement logic for incentive programs

Supplier payment and settlement mechanics shape whether Vietnam group travel programs are executable, auditable, and defensible under client governance. This actor-specific reference clarifies responsibility boundaries implied by Vietnam supplier payment terms agents - including who initiates payments, who temporarily carries supplier exposure, and how risk transfers across end client, agent, DMC, and local suppliers. It helps travel professionals justify payment schedules, set documentation requirements, and reduce execution risk when disruptions, supplier non-performance, or late client funding collide with pre-travel due dates.

1. Context and relevance for Vietnam supplier payment terms agents

For incentive buyers, payment terms are often treated as a finance detail. In Vietnam group travel execution, they function as a governance control: they determine whether services remain confirmed, whether duty-of-care continuity can be maintained, and whether procurement can defend decisions and charges when conditions change.

The practical tension is structural. Local suppliers commonly require deposits and/or full settlement before travel, while end-client settlement may be tied to internal approval cycles, confirmation milestones, or even post-program reconciliation. When these two calendars do not align, the program’s operational integrity becomes dependent on who is contractually required (and financially able) to bridge the timing gap.

This is why payment terms are a duty-of-care issue. If a hotel, transport operator, venue, or other supplier can release inventory due to missed payment cut-offs, the operational plan can fail at the point where the buyer expects continuity - arrivals, rooming, transfers, or event delivery. Even when alternate arrangements can be made, the program may incur cost uplift, service-level downgrades, or schedule disruption that then triggers reputational exposure for the seller (agent) and governance questions from the end client.

Unclear payment terms create predictable failure modes:

- Service release risk (inventory held but not secured due to deposit timing ambiguity).

- Re-confirmation exposure (suppliers request re-approval or rate changes due to late settlement).

- Reputational damage (client perception that “the program failed” regardless of root cause).

- Disputes over causation (“who caused the failure”) when funding or approvals arrive late.

The decision this section supports for agents is not “how to pay suppliers.” It is how to select payment schedules and contract language that align with the end client’s approval and funding cycle while remaining compatible with on-ground supplier requirements. The goal is to make the program executable without silently transferring interim financing exposure to a party that did not approve it.

A critical boundary to enforce: where “industry norms” end and contractual responsibility begins. Norms (for example, deposits due pre-travel) explain why suppliers behave as they do, but norms do not allocate legal responsibility for late funding, service release, or cancellation. If responsibility is not written, it will be argued during a disruption - exactly when governance needs clarity the most.

2. Roles, scope, and structural considerations

Payment terms become enforceable (or unenforceable) based on how the parties are defined and how contracts are structured. Mislabeling an actor can shift liability, distort expectations about who can enforce remedies, and create gaps in accountability.

Definitions commonly used in Vietnam group travel contracting:

- Supplier: local providers of services such as hotels, transport operators, venues, or activity providers delivering direct on-ground execution.

- DMC (Destination Management Company): intermediary coordinating group operations, including supplier contracting and supplier payments under local terms.

- Agent: B2B intermediary (for example, tour operator, incentive house, or agency) between end client and DMC, often owning the RFQ and client-facing commercial package.

- End client: the incentive buyer designing, approving, and funding the reward program.

Why mislabeling changes liability: a party described as “agent” in a commercial conversation might be treated as “principal” in a contract, which can affect who is responsible for payment default, who is entitled to refunds or credits, and who can enforce penalties for non-performance.

Structural boundary map (privity of contract) is the backbone of enforceability:

- Agent - DMC: typically governs scope, payment milestones, change control, and documentation obligations for the program delivery package.

- DMC - Supplier: governs deposits, release dates, performance obligations, remedies (penalties/credits), and service exception reporting.

- End client - Agent or End client - DMC: governs procurement constraints, approval rules, and settlement logic at the buyer level.

Privity matters because enforcement generally follows the contract chain. If the DMC is the contracting party with a hotel, the agent may not be able to directly enforce refund terms against that hotel. Conversely, if an end client expects “direct recourse” against a supplier, the contract structure must explicitly support that expectation (or explicitly reject it to avoid later disputes).

Responsibility allocation by function (conceptual, not procedural):

| Actor | Function ownership (governance-level) | Why it matters for payment terms |

|---|---|---|

| End client | Budget approval, governance constraints, funding authorization, acceptance/sign-off | Sets approval cycles and audit requirements that must be compatible with pre-travel supplier cut-offs. |

| Agent | RFQ ownership, client invoicing, alignment of client payment milestones with DMC deposit requirements | Controls the commercial timeline presented to the buyer; must prevent misalignment that forces unmanaged interim exposure. |

| DMC | Supplier contracting, interim liability while suppliers require advances, consolidation of invoices and proofs | Operationally anchors confirmations; may need to advance supplier payments to secure services, depending on contract terms. |

| Supplier | Performance delivery and invoicing obligations, notification duties for exceptions | Must comply with agreed cut-offs and exception reporting; failure impacts service integrity and dispute posture. |

A frequent governance error is failing to distinguish payment initiation from payment risk ownership.

- Payment initiation answers: “Who sends funds and when?”

- Payment risk ownership answers: “Who carries exposure if funds arrive late, if services are released, or if cancellation penalties apply?”

These can be different parties. For example, an agent may invoice the end client (initiation at buyer level), while the DMC pays suppliers (initiation at local level). If the end client pays late but suppliers require pre-travel settlement, someone will carry interim exposure. If the contract does not define who, the program becomes fragile under normal administrative delay - not only under crisis.

Settlement triggers that must be explicitly defined typically include:

- Confirmation: what constitutes a confirmed service (email? voucher? supplier confirmation number? signed function sheet?).

- Pre-travel cut-off: the date/time when services may be released or penalties escalate if payment is not received.

- Program completion: what “delivered” means for multi-component programs (arrival transfers, stay, events, departures).

- Final reconciliation: when incident-related adjustments, credits, and last-minute changes are closed and invoiced.

Contract elements that most directly affect agent exposure under Vietnam supplier payment terms agents:

- Advance/deposit thresholds: when deposits are required, and whether deposits are refundable, creditable, or non-refundable under defined conditions.

- Retention/holdback concepts: whether a portion of payment is held until completion (and what completion evidence is required).

- Cancellation triggers tied to payment dates: how late payment interacts with supplier cancellation windows and release clauses.

- Dispute resolution forum and governing law expectations: alignment between master agreements and supplier agreements (for example, references to Vietnamese law/arbitration) to avoid contradictory pathways during disputes.

3. Risk ownership and control points

In Vietnam group incentive operations, failures in the payment-to-delivery chain typically occur at control points where timing, authority, and documentation are not aligned. These are not “rare edge cases”; they are predictable stress points that should be governed in the contract and enforced through agreed artifacts.

Where failures typically occur:

- Timing mismatch: supplier pre-travel deadlines versus end client internal approval cycles. This mismatch creates pressure to “hold” services informally, which is operationally weak and hard to defend in procurement review.

- Documentation gaps: unlogged deviations, missing sign-offs, and unclear authority to approve changes. The operational team may deliver a workaround, but governance cannot defend costs without an audit trail.

- Contingency gaps: insufficient clauses for overbooking, force majeure, or supplier no-show remedies. Without predefined remedies and decision authority limits, disputes become subjective at the worst moment.

Risk ownership scenarios (governance-focused allocation + required control points):

Primary risk owner (operational continuity): DMC. Secondary (client communication alignment): Agent.

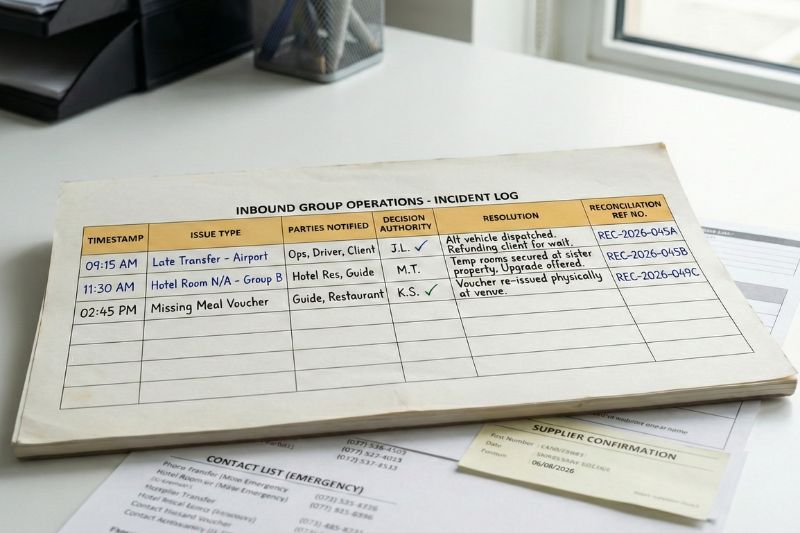

Control points to require: escalation time expectation (for example, DMC to agent within a defined window), supplier contingency buffers embedded in contracts where relevant, and an incident log with timestamps to support later reconciliation and charge defensibility.

Primary risk owner (backup strategy): DMC. Supplier duty: immediate notification.

Control points to require: overbooking/alternate accommodation terms, a deviation report documenting the variance and remedy, and acceptance/sign-off that captures who approved the alternative and on what basis.

Primary risk owner (on-site duty-of-care response coordination): DMC. Secondary (insurance liaison interface): Agent.

Control points to require: defined escalation timeline to agent/end client, documented approvals where cost-bearing decisions are made, and a medical reporting trail sufficient for later claims, audit, and reconciliation.

Primary risk owner (alternate mobilization responsibility): DMC. Supplier duty: maintenance reporting and immediate exception notification.

Control points to require: timestamped evidence (photos, location/time references where appropriate), a defined client-facing updates channel via the agent, and logging discipline so that delay impacts are measurable and attributable.

Primary risk owner (rescheduling authority within agreed parameters): DMC. Approval boundary (commercial/program impact): agent/end client must be explicit.

Control points to require: force majeure definition in the applicable agreements, documented advisories (for example, official notices where available), and a written record of options presented and selections approved.

Primary risk owner (enforcement and replacement execution): DMC. Approval boundary (substitutions impacting budget/brand): agent/end client must be explicit.

Control points to require: breach notice, evidence of supplier failure, replacement authorization where needed, and refund/credit proof to support reconciliation and any downstream client invoicing adjustments.

Preventive controls to specify in master agreements (what must exist, not how to execute):

- Escalation ladder: who-to-who, decision sequencing, and explicit notification windows for high-impact incidents.

- Decision authority limits: what the DMC may change without re-approval, and what must be escalated to the agent/end client.

- Required artifacts: incident logs, deviation reports, written amendments for changes, and final reconciliation sign-off.

Auditability standard: the agreement should define the retention period for contracts, invoices, proofs of payment, deviation reports, and sign-offs - and identify who holds the system of record. If the agent is expected to defend charges to the end client, the agent must have contractual access to the artifacts required to do so.

4. Cooperation and coordination model

Payment terms become workable when coordination across actors is disciplined. Incentive programs fail less often due to “bad intent” and more often due to unmanaged handoffs - especially between RFQ, confirmation, deposit deadlines, and last-minute changes.

Coordination flow across actors (handoffs and information discipline):

- RFQ intake - scope baseline, assumptions, and authority constraints are declared early (including payment milestones and cut-offs).

- Confirmation - confirmation is defined and documented; supplier deposit requirements are mapped to buyer funding milestones.

- Supplier deposits - commitments are triggered only after the required approvals and documented authorization conditions are met.

- Operational delivery - incident governance follows escalation ladder; deviations produce signed artifacts.

- Reconciliation - proofs and adjustments are consolidated; final settlement follows defined completion and sign-off rules.

Communication governance between agent and DMC is a control system, not a preference:

- Single point of contact rules: named operational and commercial contacts reduce decision ambiguity during disruptions.

- Decision-maker designation: who can approve spend, substitutions, and itinerary changes (and within what limits).

- No verbal-only changes: verbal instructions may be operationally necessary, but they should be confirmed in writing within an agreed timeframe to remain auditable.

- Pre-authorization discipline: alignment on what the agent must obtain from the end client before authorizing supplier commitments that trigger deposits or penalties.

Supplier coordination expectations managed by the DMC (as the contracting party) should be explicit because supplier behavior drives many “surprise” costs:

- Notification duties: what exceptions must be reported immediately (overbooking, service failure, late arrival impacts).

- Substitution permissions: what substitutions are allowed, what requires approval, and what documentation is mandatory.

- Service-level exception reporting: minimum content for a deviation report and the time window to deliver it.

Change-control model that protects all parties:

- Re-approval triggers: term extensions, increased advances, supplier substitutions, or changes that materially affect budget, duty-of-care exposure, or buyer procurement constraints.

- Dual sign-off logic (agent/DMC): written amendment required to ensure both the selling party and the local contracting party can defend the change.

- Documenting client approvals without exposing confidential procurement data: approvals can be captured as summarized authorizations (what was approved, by whom, when, within what limit) without transmitting internal buyer documents that should remain confidential.

Reconciliation and closure model:

- Post-program sign-off boundary: define what constitutes “completion” (delivered services plus documented deviations).

- Open disputes: specify what disputes remain open after completion (for example, pending supplier credit) and how they are tracked.

- Final settlement due: define when final settlement is due relative to reconciliation deliverables and sign-off.

5. Payment timelines, advance deposits, and retention clauses in Vietnam DMC operations and planning

Payment timelines in Vietnam group travel programs can be understood as a conceptual sequence: contracting → deposit → pre-travel balance → completion → reconciliation. The precise dates vary by supplier, but the governance challenge is consistent: supplier due dates often occur ahead of travel while buyer settlement may occur later.

Typical sequencing of supplier payments in Vietnam group travel programs (conceptual):

- Contracting: supplier terms define deposit due date and release clause; the DMC (as contracting party) accepts these terms on behalf of the program structure.

- Deposit: used to secure inventory and reduce supplier cancellation risk.

- Pre-travel balance: ensures full confirmation for high-demand dates and reduces last-minute service release exposure.

- Completion: operational delivery occurs under the assumption that payment milestones have preserved confirmations.

- Reconciliation: deviations, credits, penalties, and last-minute changes are consolidated with supporting artifacts.

How advance payment thresholds reduce supplier non-performance risk but increase interim financing exposure:

- Risk reduction: deposits can strengthen service commitment and reduce the likelihood of supplier release or repricing.

- Exposure increase: the party advancing funds carries exposure if the end client’s payment is delayed, disputed, or constrained by procurement rules.

Retention/holdback logic (portion held until completion) is a governance tool, not a guarantee. It is typically designed to:

- maintain leverage for service quality and fulfillment compliance,

- ensure documented closure for disputes and deviations,

- create a structured incentive for timely completion of reporting and reconciliations.

Allocation of interim financing exposure is the core question in Vietnam supplier payment terms agents. Late end-client payment can shift risk to the agent, the DMC, or remain with the end client - but only if the agreements state it clearly.

Generic scenario framing (for governance review):

- Scenario: A hotel contract requires an advance payment to secure rooms. The end client’s internal payment cycle delays settlement beyond the supplier’s pre-travel due date.

- Key governance question: which agreement states who carries the interim exposure (agent-DMC master terms and/or end client-agent terms), and what happens to service confirmation if funds are not received by the cut-off?

- Required clarity: whether the DMC is authorized (or obligated) to advance funds, whether the agent must fund, or whether services may be paused/released until payment is received - and how this is communicated and documented.

Dispute pathways tied to payment terms should distinguish payment disputes from performance disputes:

- Payment dispute: disagreement about amounts due, timing, or application of deposits/credits. Governance requirement: invoices, payment proofs, and contractual basis for due dates and penalties.

- Performance dispute: disagreement about whether services were delivered as contracted. Governance requirement: incident logs, deviation reports, sign-offs, and supplier breach notices where applicable.

Arbitration/legal forum references matter because inconsistencies across agreements create practical dead-ends. If a master agreement points to one dispute pathway and supplier agreements point to another, responsibility for pursuing remedies becomes unclear - and the party facing the end client may be left carrying reputational and financial exposure without an enforceable route to recovery.

Operational/logistics linkage (mandatory): payment milestones directly affect operational release dates and planning integrity. Agents should treat payment dates as operational cut-offs for:

- rooming lists (finalization and acceptance rules),

- transport allocations (fleet assignment and backup provisioning),

- venue confirmations (function sheet finalization, setup times, and guaranteed minimums where applicable),

- supplier staffing (guides, coordinators, and technical staff where contracted).

Partner success/case-study potential (generic, non-promotional): if the end client requires evidence that the program was governed defensibly, the following metrics support “program defensibility” without relying on subjective satisfaction:

- Confirmation stability rate: proportion of services that remained confirmed without forced re-confirmation due to missed payment cut-offs.

- Incident documentation completeness: proportion of incidents with a timestamped log and required attachments.

- Deviation sign-off compliance: proportion of deviations with documented acceptance by the authorized party.

- Reconciliation turnaround time: time from program completion to delivery of a reconciled statement with supporting proofs (measured consistently within the project’s governance standard).

Primary CTA (evaluation stage)

If you need a Vietnam incentive program quotation aligned to supplier deposit realities and audit-ready documentation requirements, we can price with explicit payment milestones, decision authority boundaries, and reconciliation artifacts.

Get a Quote (12-60 Minutes)6. FAQ themes (questions only, no answers)

- Who is the contracting party with hotels and transport suppliers in Vietnam group travel programs - agent or DMC?

- Under Vietnam supplier payment terms agents, who carries risk if the end client pays late but suppliers require pre-travel deposits?

- What payment milestones should be tied to confirmation, pre-travel cut-off, and final reconciliation?

- What documentation is required to defend a charge caused by disruption (weather, overbooking, transport failure)?

- What escalation timeline should be defined for medical incidents and major service deviations?

- When is a supplier substitution allowed without end-client re-approval, and how should it be logged?

- How should force majeure be defined so rescheduling authority is clear and auditable?

- What records must be retained post-program to meet governance and audit expectations?

- How can agents validate a DMC’s capacity to advance supplier payments without creating procurement conflicts?

- What are the minimum change-control triggers that should require written amendments and dual sign-off?

EN

EN