Vietnam Group Airport Arrivals for MICE Planners | Risk

Why Large Groups Fail at Airports (and How Professionals Prevent It)

Large group airport arrivals in Vietnam fail not because planners “miss details,” but because airport processes optimized for individuals create divergence when 20-200 passengers hit immigration, baggage, and transfers at once. This actor-specific, authority-focused reference explains why large groups fail at airports (and how professionals prevent it) by clarifying who owns which inputs, decisions, and escalation steps across agency, DMC, suppliers, and the end client. It helps travel professionals set realistic day-1 timelines, protect duty-of-care, and create an audit trail when queues, visa variability, or luggage gaps threaten program continuity.

1. Context and relevance for large group airport arrivals in Vietnam

For MICE and incentive groups, the airport is a day-1 program risk multiplier because downstream milestones are chained: immigration affects baggage, baggage affects customs exit, customs exit affects coach roll, and coach roll affects hotel check-in waves, meal timing, and venue access. When any upstream step becomes variable, the whole arrival-day plan becomes fragile.

Airports are designed to process individuals. In a group context, that design creates predictable failure modes: different passengers clear at different speeds (queue divergence), the group regroups in bottlenecks (arrival hall or carousel edges), and the transfer waits on the slowest exception unless rolling rules exist. The result is not “one delay,” but compounded delay across multiple dependencies.

What is at stake for travel professionals is governance, not comfort: client confidence in day-1 control, meeting start times, duty-of-care exposure when subgroups split, and downstream knock-ons to suppliers (hotel staffing and room readiness, restaurant set times, venue access windows, and production schedules).

Common trigger conditions in Vietnam that amplify variance include mixed visa types within one manifest (e-visa, visa exemption, visa-on-arrival and related processing variability), peak-hour arrival banks and widebody clustering, and luggage reconciliation gaps that remain invisible until coach loading or hotel arrival.

A practical decision lens for planners is to choose between a “soft landing” and an “active arrival-day program” based on controllability, not ambition. If immigration variability and baggage variance are structurally high (mixed visa types, peak banks, tight onward timing), a soft landing reduces downstream breach risk. If controllability is higher (homogeneous visa types, stable arrival wave, conservative buffers), an active arrival-day program can be governed more credibly.

2. Roles, scope, and structural considerations

Definition - group airport arrival: Coordinated handling of 20+ passengers through immigration, baggage claim, customs, and transfer. In Vietnam, subgrouping by visa type is a structural requirement because different visa paths clear at different speeds and may involve different processing points.

Definition - fast-track service: Escort from the immigration/visa area through priority processing to baggage claim, used to reduce queue variability. Boundary condition: fast-track can reduce immigration variance, but it does not eliminate baggage claim time or customs variability.

Definition - luggage reconciliation: Pre-tagged bag count and owner confirmation at carousel and coach loading. This is not only an operational control; it is a governance control because it creates defensible evidence of handover status and reduces “silent losses” that emerge later.

Responsibility boundaries by actor should be agreed as early as RFQ stage to avoid ambiguity on day-of-arrival:

End client / MICE organizer

- Owns: passenger data inputs (manifest, nationality/visa mix, special needs), emergency contacts, approval of arrival-day program style (soft landing vs active).

- Supports: compliance readiness through internal communications (passport validity and document readiness expectations).

Travel agency / tour operator

- Owns: RFQ framing, briefing distribution, client updates and approvals, change-control discipline.

- Supports: visa tracker coordination and deadline enforcement across travelers and stakeholders.

DMC (on-ground operator)

- Owns: flight monitoring, meet-greet positioning, subgroup sorting logic, supplier ETAs, exception handling (for example, lost bag reporting), documentation pack for arrivals.

- Supports: risk register inputs and escalation routing to agency/client for approvals that impact timeline or duty-of-care posture.

Suppliers (airport services, transfer providers, hotels)

- Owns: delivery of scoped services (fast-track, portering if included), vehicle readiness, group check-in process.

- Supports: rapid delay reporting to the DMC and service recovery implementation within the scoped service model.

Structural considerations that shape outcomes (governance-level, not execution detail):

- Visa variability is the primary flow splitter - it creates parallel clearance speeds and increases regroup complexity.

- Single-coach dependency - without pre-agreed rolling rules, one late subgroup can hold 30-50 passengers “hostage” against the day-1 timeline.

- Documentation readiness is a control - manifest accuracy, visa tracker completeness, and rooming list finality determine how defensible decisions are when variance occurs.

3. Risk ownership and control points

Where failures typically occur in the airport chain is consistent across large groups because the chain contains multiple points where individual variance becomes group delay:

- Pre-arrival: incomplete visa tracker, inaccurate manifest, missing special-assistance flags.

- Immigration/visa processing: mixed visa types create different queue speeds and potential rework loops.

- Baggage claim: untagged ownership, carousel dispersion, late bags that delay coach roll.

- Customs/exit: regroup bottlenecks and missing headcount confirmation.

- Transfers: insufficient luggage capacity assumptions and traffic buffers misaligned to hotel zone or venue timing.

Risk ownership matrix (conceptual mapping) should be explicit, because “everyone is responsible” typically becomes “no one is accountable.” The following mappings frame primary ownership and control points without shifting responsibility away from the appropriate actor.

Flight disruption / late arrival

- Primary owner: DMC for monitoring and repositioning. Secondary: agency for client communications discipline.

- Control points: flight watchlist; agreed buffers by peak-hour and visa mix; documented revised ETA chain.

Hotel overbooking / rooming mismatch

- Primary owner: DMC for reconfirmation and check-in planning. Secondary: hotel for inventory delivery.

- Control points: rooming list cut-off; master folio alignment; pre-alert process; fallback space plan.

Medical incident

- Primary owner: DMC for response coordination. Secondary: tour leader for first report.

- Control points: completeness of emergency contacts; subgroup supervision rules; incident reporting format.

Transport disruption (coach breakdown / traffic delay)

- Primary owner: DMC for capacity verification and backup dispatch. Secondary: transfer supplier.

- Control points: luggage load assumptions; routing buffers by zone; alternate vehicle triggers.

Weather disruption

- Primary owner: DMC for indoor backup advisories and supplier re-timing. Secondary: agency/client for program flex approval.

- Control points: seasonal buffers; windowed ETA communication; variance logging.

Supplier no-show (guide/assistant/fast-track)

- Primary owner: DMC for pre-confirmation and backup staffing. Secondary: supplier.

- Control points: named staffing roster; meet point definition (arrival hall vs immigration-side); contingency activation record.

Escalation logic and evidence standards make accountability workable. Two principles govern whether escalation works under pressure:

- Timeliness expectations: who must be informed, by when, for landing delays and missed service milestones. A usable model is to define an immediate notification window for material timeline changes and require each update to include a revised forecast, not only the issue.

- Evidence quality: what documentation is needed to justify decisions to the client - timestamps across key milestones (landing, immigration exit, bag complete, coach roll), photos for baggage tag issues where relevant, and a signed headcount confirmation at agreed checkpoints.

Use the framing “Why Large Groups Fail at Airports (and How Professionals Prevent It)” as a governance checklist - not a blaming exercise. The objective is to allocate responsibility for inputs, decisions, and escalation steps before day-1 so exceptions can be handled without ad hoc negotiations at the curb.

4. Cooperation and coordination model

Coordination flow from RFQ to day-of-arrival is primarily a handoff discipline problem. If the “who provides what, by when” chain is unclear, the airport becomes the first place it fails visibly.

- Agency → DMC: group profile, service scope, arrival-day intent, and client constraints (meeting start times and duty-of-care rules).

- DMC → Agency: routing advisory, visa risk flags, recommended buffer logic, and the arrival pack deliverables needed for field control.

- Agency → End client: approvals for program style, change-control triggers, and the escalation contact tree (who can approve timeline impacts).

- DMC ↔ Suppliers: staffing confirmations, vehicle staging, hotel check-in readiness, and windowed ETAs to align labor and space.

Communication standards that reduce friction should be simple enough to survive day-of conditions:

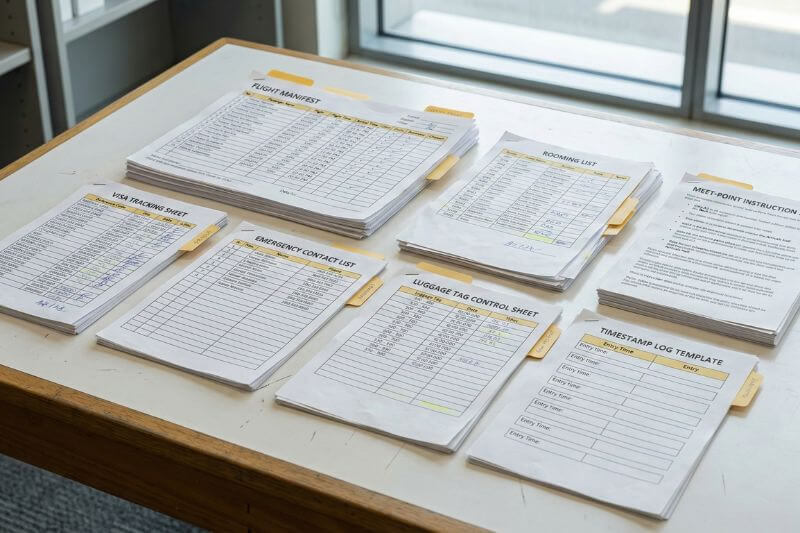

- Single source of truth: version-controlled manifest, visa tracker, and rooming list - one controlled file set, not parallel copies.

- Windowed ETA practice: communicate early/likely/late ranges rather than a single fragile time, reducing hotel and venue pile-ups when queues vary.

- Regroup rules pre-agreement: who waits where, when the main group can move, and how exceptions are supervised so duty-of-care does not degrade when the flow splits.

Change-control model should define what triggers re-approval so operational changes do not become governance disputes:

- Visa mix shift thresholds, flight bank alterations, group size variance, arrival-day program style switch.

- Joint review responsibilities (agency/DMC) and when client sign-off is mandatory due to timeline, cost, or duty-of-care implications.

Partner success / case-study potential (generic, non-promotional): Clear role boundaries and timestamped logs enable post-event auditability and continuous improvement. “Success evidence” for stakeholders is usually governance evidence: fewer disputed handovers, fewer unexplained day-1 variances, and documented duty-of-care compliance, rather than anecdotal satisfaction signals.

5. Vietnam group airport arrival playbook: visa-split flow control and luggage reconciliation as the highest-leverage controls

Vietnam airports can process individuals efficiently while groups fail under mixed visa conditions. The mechanism is structural: if subgroup rules are not pre-set, one delayed visa-processing passenger can hold an entire coach movement because the transfer plan is often built around a single synchronized regroup moment.

Pre-flight governance controls (inputs and compliance readiness) are the highest ROI controls because they prevent predictable queue failures:

- Visa tracker as a mandatory artifact: name, nationality, visa type, and document readiness status. This is required to design subgrouping and to forecast variance under peak conditions.

- Passport/document readiness checks: validity, blank pages, and matching personal details. These are preventable failure classes that otherwise convert into on-arrival exceptions.

Arrival flow control principles owned by on-ground operations (conceptual sequencing) focus on preventing divergence from becoming delay:

- Subgroup sorting by visa type: named subgroup leads and defined regroup points so mixed visa processing does not create unmanaged separation.

- Fast-track placement logic for mixed-type manifests: used to smooth immigration-side variability where appropriate. Limitation disclosure is essential: it cannot guarantee baggage timing and does not remove customs variability.

Luggage reconciliation framework (control intent and accountability) exists to prevent unnoticed losses that surface later as reputational and duty-of-care issues:

- Pre-tagging and bag-count discipline: reduce the chance that a bag is left behind without detection.

- Dual confirmation points: at carousel and coach loading, with a recorded count and owner confirmation logic.

- Exception handling rules: incomplete baggage is logged, reported, and delivered with a defined update cadence, without leaving passengers unsupported or unclear on next steps.

Duty-of-care boundary rules must be explicit because mixed visa processing naturally splits the group:

- No-lone-waiting principle: named contacts per subgroup and supervised exceptions, so no passenger is left without an accountable point of contact.

- Lost-bag plan ownership: who files, who tracks, who updates the passenger and the client, and what proof is retained (tag images, timestamps, delivery status).

Generic peak-bank scenario walkthrough (non-story)

Condition: a mixed visa group arrives during a widebody cluster. Governance response: split the group by visa type with named leads, define separate processing paths, and use regroup points that do not block the main flow. Operational coordination response: send windowed ETAs to the hotel and pre-alert check-in readiness, preventing a single-time “pile-up” when the clearance time spreads. Audit response: maintain a timestamped milestone log and document decisions (for example, when regrouping occurs and when transfers roll) so day-1 variance is explainable rather than disputed.

6. FAQ themes (questions only, no answers)

- Who is accountable when a late visa-on-arrival passenger delays the entire group transfer?

- What inputs must the end client provide for the DMC to own airport flow control credibly?

- When is fast-track appropriate for mixed-nationality groups, and what limitations should be disclosed?

- What are the minimum documentation artifacts for a defensible arrival-day audit trail?

- What change-control triggers require client re-approval (visa mix, flight bank, pax variance, program style)?

- How should agencies and DMCs define escalation timelines after landing delays or missed service milestones?

- What duty-of-care rules apply when subgroups split across immigration and baggage timelines?

- How should luggage reconciliation be structured to reduce unnoticed losses without slowing the group?

- Who owns hotel overbooking risk, and what pre-arrival confirmations reduce rooming mismatches?

- What is the best governance approach to “soft landing” vs “active arrival-day program” decisions for MICE groups?

EN

EN