Vietnam DMC White-Label Execution | Change Control & RACI

White-Label Execution in Vietnam: How Brand Protection Works on the Ground

White-label execution in Vietnam group travel is often adopted so agencies can protect client-facing brand consistency while delegating on-the-ground delivery to a local DMC. This industry-wide reference clarifies where responsibility starts and ends across agency, DMC, suppliers, and end client - especially when operational realities (supplier substitutions, access restrictions, disruptions) force changes. It helps travel professionals decide how to structure accountability, what governance documents must exist, and which execution risks most commonly cause brand damage through mixed messaging, undocumented changes, or visibility gaps.

1. Context and relevance for White-Label Execution in Vietnam: How Brand Protection Works on the Ground

Brand protection becomes an operational governance issue in Vietnam group travel because delivery is inherently multi-party and condition-dependent. A single program can involve multiple hotels, transport providers, guides, venues, and access-controlled sites, each with timing constraints and operational rules that can change without notice. Tight access windows (airports, hotel loading bays, venues, piers) amplify the cost of ambiguity: if the on-site team improvises without an approval pathway, the agency can inherit client-facing inconsistency even when the program design was sound.

Typical failure modes that affect agencies most are not “service quality” in the abstract, but governance breakdowns that create reputational exposure:

- Inconsistent client messaging - different people explaining different plans, or changes communicated in different language at different times.

- Silent changes - supplier substitutions or timing changes implemented on the ground without a documented approval trail.

- Unclear escalation - guides or coordinators escalating to the wrong party (or too late), leading to reactive decisions that contradict the agency’s client promises.

- Limited real-time visibility - the agency cannot answer “where is my group?” or “what changed and why?” with confidence during live operations.

White-label execution is appropriate when the agency’s primary requirement is consistent client-facing branding and controlled communication, while delegating on-site coordination and duty-of-care response to a DMC operating within agreed authority. It is less appropriate when direct supplier contracting is required for governance or procurement reasons, or when client-direct DMC contact becomes unavoidable (for example, certain MICE production environments, specialist permits, or venue relationships that require named responsible parties on-site). In those cases, the operational model should be disclosed and structured rather than assumed.

A practical decision lens for travel professionals is to separate two types of control:

- Control of message - who can communicate what to the client, in which formats, and with which escalation thresholds.

- Control of execution - who can make time-critical operational decisions, mobilize backups, and coordinate suppliers under pressure.

What can often be delegated safely is on-site recovery and supplier enforcement within pre-agreed boundaries. What typically must remain with the agency is brand messaging, disclosure rules, and final approval for any change that impacts client promise, cost, or named deliverables.

2. Roles, scope, and structural considerations

Definition (working baseline): White-label execution is structured delivery where a DMC handles on-site program implementation (hotels, transport, guides, events) under the agency’s branding, with controlled client visibility. Commonly, this includes rebrandable client-facing documents and separate internal operational appendices used for risk control and delivery governance.

Parties and boundaries (industry-wide baseline):

- Agency: program design, selling, client communications, final approvals. Owns brand messaging and disclosure rules.

- DMC: feasibility checks, supplier contracting and coordination, on-site duty of care, incident handling, 24/7 escalation, and operational documentation control.

- Suppliers: contracted service delivery. No program-wide decisions. No client contact unless explicitly authorized.

- End client: provides manifest/preferences and feedback. Does not manage operations or escalations.

Responsibility boundary principles that protect the agency brand:

- Single source of truth for the client-facing schedule (agency-branded), paired with a separate operational appendix that includes buffers, access notes, and constraints.

- Authority clarity on who can authorize:

- (a) cost changes

- (b) supplier swaps

- (c) timing changes

- (d) client-facing messaging changes

Scope exclusions commonly required for clean accountability: Air ticketing and non-destination logistics typically remain outside DMC ownership unless contracted explicitly. Even when out of scope, air disruptions often drive ground changes, so interfaces must be defined (who informs whom, which decisions require approvals, and how cost impacts are handled).

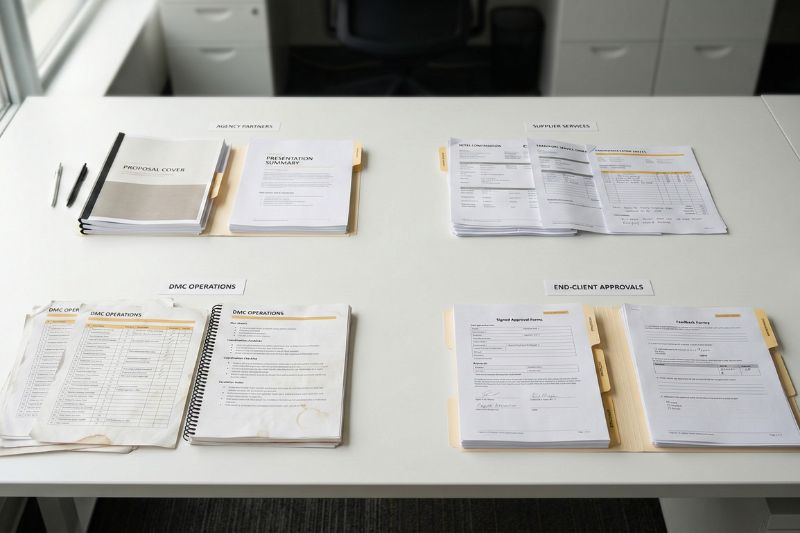

Structural artifacts that should exist before confirmation:

- A responsibility map / RACI-style responsibility statement covering approvals, escalation, and client communication rules.

- A rebrandable itinerary (client-facing) and a separate version-controlled operations sheet (internal delivery governance).

3. Risk ownership and control points

Where failures typically occur across the group lifecycle:

- Pre-trip data integrity: manifest completeness, medical flags, rooming lists, VIP handling requirements, dietary/access needs, and cut-off dates.

- Day-of operations: meet points, staging and flow, access limits, supplier punctuality, and loading/unloading constraints.

- Mid-program changes: weather, traffic, capacity constraints, substitutions, and sequencing changes that affect client perception.

- Incident response: medical events, safety concerns, lost items, complaints - plus post-incident documentation needed for defensibility.

Risk ownership by scenario (primary vs. secondary ownership):

| Scenario | Primary owner (typical) | Secondary owner (typical) | Control point that should be pre-defined |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flight disruption / late arrival | DMC (ground recovery: meet, staging, flow) | Agency (reroute approval when client/cost impact applies) | Confirmed meet points, parking constraints, contingency timings in ops sheet |

| Hotel overbooking / rooming mismatch | DMC (supplier enforcement, alternatives) | Agency (rooming list provision, approvals) | Rooming cut-offs, loading bay/shuttle needs, change-log rule |

| Medical incident | DMC (coordination, translation, safe-hold, local pathways) | Agency (insurance liaison, client approvals where required) | Medical flags in manifest, escalation and documentation requirements |

| Transport disruption (breakdown/traffic) | DMC (replacement dispatch, buffer logic) | Supplier (initial remediation per contract) | Vehicle plan, peak-hour buffers, shuttle options, approval thresholds |

| Weather disruption | DMC (activate contingencies) | Agency (approve client-facing change decisions) | Contingency matrix and pre-agreed alternative pathways |

| Supplier no-show | DMC (backup mobilization, documentation) | Agency (only if a named supplier is promised to client) | Substitution windows, equivalency criteria, and notification rules |

Preventive controls that reduce brand risk (governance-focused):

- Confirmed meet points, access/parking constraints, and buffer assumptions captured before travel - not discovered during live operations.

- Substitution rules agreed before confirmation (equivalency criteria, time windows, and thresholds that trigger agency approval).

- A pre-agreed escalation tree and a written “who speaks to the client” rule to prevent mixed messaging under pressure.

Escalation logic and auditability: White-label execution remains brand-safe when escalation routes are explicit and evidenced. A typical expectation is a 24/7 duty channel with role-based escalation (guide -> ops lead -> duty manager -> agency), supported by timestamped incident logs, recovery memos, and sign-offs. The objective is to reduce post-event disputes by creating a consistent audit trail of what happened, who decided, and what was communicated.

4. Cooperation and coordination model

Communication discipline in a white-label environment: The most common governance failure in white-label delivery is not operational error, but communication leakage. The model typically requires separation between client-facing communications (agency-controlled) and operational communications (DMC-controlled). Where guides or coordinators interact with participants, approved scripts and “single voice” rules reduce the risk of mixed messaging, especially during disruptions and substitutions.

Operating cadence that supports oversight without client exposure:

- Daily operational check-ins and push updates so the agency is aware of deviations, upcoming risks, and any approvals needed.

- Shared live operations group usage (or equivalent) to provide visibility on status and location without breaching white-label boundaries or creating parallel client communication channels.

Handoffs and dependency points that require explicit agreement:

- Data handover: manifest, VIPs, medical flags, rooming list cut-offs, dietary/access needs - including who can update what, and until when.

- Approval handover: what the DMC can execute autonomously (within constraints) vs. what requires agency confirmation (cost, timing, named deliverables, client messaging).

- Supplier management: DMC as sole contracting/enforcement interface; any conditions for supplier-direct coordination should be explicitly authorized to avoid unmanaged commitments.

Partner success/case-study potential (generic, non-promotional): For institutional learning, the most useful capture points are patterns rather than anecdotes - recurring change-log categories, common incident types, and supplier reliability notes. A post-tour operational pack can support program improvement and client justification (for example, explaining why a change occurred and which approvals were obtained) without revealing DMC identity, provided the documentation is structured for auditability rather than marketing.

5. Vietnam DMC operations and planning governance: briefing packs, change control, and incident audit trails

Briefing pack architecture (what should exist in an agency-branded vs. internal document set):

- Rebrandable schedule for client use: the participant-facing itinerary and service promise, aligned to the agency’s messaging rules.

- Operational appendix for risk control: route timing logic and buffers, access notes (coach restrictions, loading bay constraints), supplier plan, contact tree (guide-ops-management-agency), contingency matrix, and inclusions/exclusions defined in operational terms.

Change-control rules that preserve brand integrity:

- Standard triggers for re-approval: timing shifts, cost impacts, supplier swaps, and any client-facing message change.

- Minimum change-log fields: change_id, timestamp, reason_code, proposed action, approval owner, and execution confirmation.

- No execution without unified sign-off: when a change crosses an approval threshold, execution should not proceed until the responsible approver confirms. This is the simplest control to prevent undocumented changes and post-event disputes.

Incident logging and evidence requirements (duty-of-care defensibility):

- What must be recorded: timeline, decisions, approvals, third-party reports (where applicable), and recovery actions.

- Storage and access expectations: 24/7 retrievability, version control, and a post-tour archive that can be referenced for audits, claims, and program redesign.

Compliance-sensitive operational controls (Vietnam-specific considerations to verify at time of operation):

- Guide assignment documentation and licensing/rotation requirements as applicable under current Tourism Law interpretation (verify at time of operation).

- Supplier contract substitution clauses and the documentation expected when substitutions occur (assignment letters, handover notes, substitution records).

- Permits, venue rules, airport/hotel access limitations that may change and must be reconfirmed close to arrival.

6. FAQ themes (questions only, no answers)

- Who is the primary risk owner in a white-label model when something goes wrong on the ground?

- What governance documents should exist to separate agency branding from operational control?

- Which changes require agency approval versus DMC autonomous execution?

- How should change logs be structured to avoid disputes and protect client trust?

- What is the recommended escalation path for medical incidents and who controls client messaging?

- How can agencies maintain real-time visibility (where is my group?) without breaking white-label boundaries?

- What supplier substitution rules should be agreed before confirmation (equivalency, timing windows, thresholds)?

- What elements must be re-verified close to departure in Vietnam (access rules, permits, guide requirements)?

- What should be included in a post-tour operational pack to support audits, claims, and future program design?

- How should responsibilities be stated when air arrangements are outside the DMC scope but affect ground operations?

EN

EN